Notes on Broad-Chested Leaders

At the point of arrest by Stalin's eager lackeys, the poet could easily have renounced his work. But Osip Mandelstam looked death in the eye, and refused to surrender his authorship.

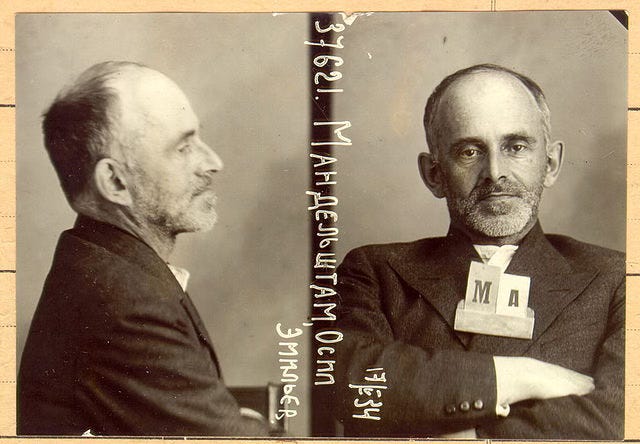

A prison photograph of Osip Mandelstam from his criminal file, dated May 17th, 1934.

The verse in question was not his most polished or most delicate; it had certainly not been committed to paper. Osip Mandelstam recited the lines among literary friends from memory.

Then one of them wrote them down, and informed the secret police.

The poem was an invective aimed at Stalin, and his deadly ‘repressions’ - the euphemistic name still given to systematic persecution and state-sanctioned murder by the communists - that were picking up fearful pace in the early 1930s.

When the NKVD agents came to his flat, bearing the transcript of the poem, Mandelstam was fully aware of the cost of scorning the Great Leader. He had, still, the choice to forswear the piece - there was no proof, after all, that he was the author. But as a matter of principle, he refused to do so.

This is how I have tried to render the poem in English (though I cannot make it scan and rhyme as Mandelstam’s original, which thumps its stanzas into the listener):

Мы живем, под собою не чуя страны…

We live not feeling the country beneath us,

Our talk cannot be heard ten paces behind us,

But if you even have the least thing to say,

You must mention the Kremlin Caucasian.

His fat fingers, wormlike and greasy,

And words, freighted with hundred pound truths,

Those cockroachy whiskers that break out in laughter,

And the tops of his boots, which are gleaming.

Around him, a rabble of thin-necked authorities;

He conjures the service of half-human men.

Some whistle, or meow, and some snivel,

While he alone mutters and prods.

Like horseshoes, he forges decree on decree -

Someone gets it in the groin, someone in the face,

Another in the brow, and one in the eye.

Killing for him is as sweet as a berry.

How broad is the chest of the Ossetian man.

1933

(Is it trite to state out loud the sense of the poem today? The moral cretinism of those who cheer for Putin, today’s broad-chested, bare-chested horseman?)

Mandelstam was detained. His friends lobbied for his life. Boris Pasternak contacted the legendary Bolshevik, Nikolai Bukharin, who appears to have interceded at the highest level. A probable death sentence was avoided, and exile enforced in its place. Yet the poet kept writing.

A few years later, at the height of the purges, the head of the Writer’s Union, Vladimir Stavsky, invited Mandelstam to enjoy a break in a residence outside Moscow, and to enter his trap: an arrest at a dacha would create less fuss than in a busy city apartment block.

Mandelstam’s erstwhile protector, Bukharin, was arrested, disgraced, and locked in pre-trial detention on March 15th, 1938. The following day, Stavsky denounced Mandelstam to the secret police chief. In May, he was arrested, given no time to pack clothes, and charged with counter-revolutionary activity, then sentenced in August, and shipped to serve a five-year sentence near Vladivostok, in the far east of Russia at the Chinese border.

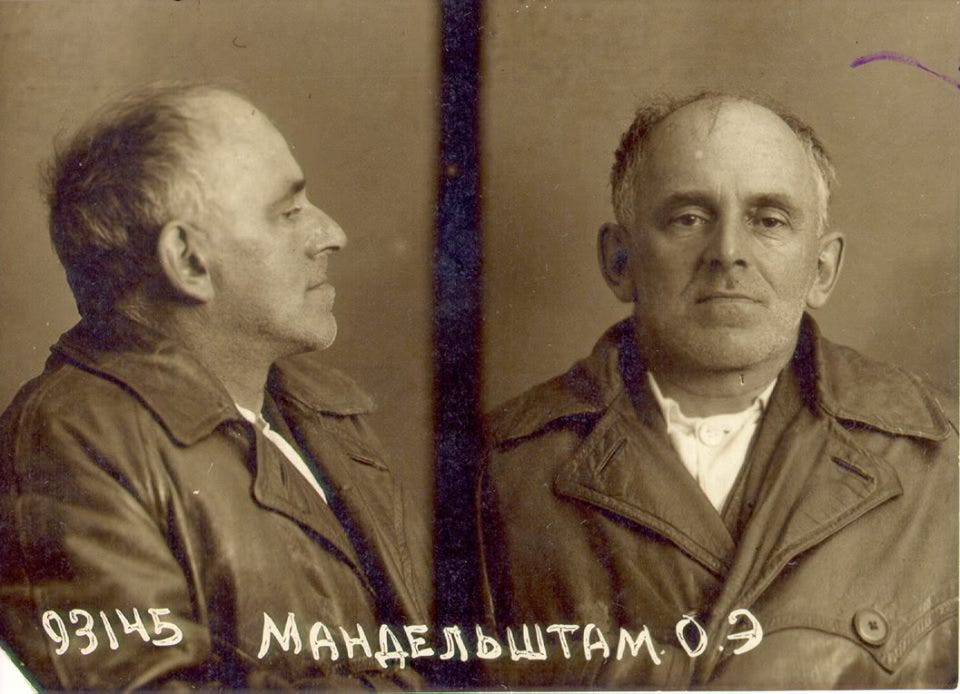

A prison photograph of Mandelstam from mid-1938

“My health is very bad, I'm extremely exhausted and thin, almost unrecognisable, but I don't know whether there's any sense in sending clothes, food or money. You can try all the same, though. I'm very cold without proper clothes.”

His last letter, to his brother, was posted from the railway station at a transit camp close to the city.

Mandelstam kept composing poetry. His health, mental and physical, was failing: he feared poisoning, and refused prison rations. For the sake of a piece of bread, he offered to recite to inmates the famous Stalin verses that had caused him to be arrested the first time. One fellow prisoner, ‘Physicist L.’, recounted a reading in the camp by Mandelstam:

“On the top bunk a candle was burning. In the middle of the dormitory was a barrel, and on the barrel were opened tins and white bread. For a starving camp, it was unheard of hospitality. Among the ruffians was a man in a leather coat. He was reading poems… They listened to him in total silence. Sometimes they asked him to repeat a poem… I recognised Mandelstam. The prisoners gave him bread and conserves, and he ate calmly - evidently, it was only official rations that he feared.”

A bronze of Mandelstam, cast wearing the leather coat, was erected in Vladivostok in the late 90s, at the dusk of the democratic experiment. It has been vandalised more than once, and was moved to a square at the university, where it may be safe for the time being.

Photo credit: Igor/TripAdvisor

Mandelstam’s poetry runs like a golden thread through the ‘Silver Age’ of Russian art that blazed aflame before Socialist Realism’s gauntleted hand snuffed it out. The work is often colloquial, yet brittle and transcendent, like this poem I translated almost two decades ago, when the trajectory of Putin’s worldview was feared but not yet fully realised:

Возьми на радость из моих ладоней…

Accept for joy, from these my hands,

A little sunshine, a little honey,

As Proserpina’s bees require of us.

One can’t untie an unmoored boat,

Nor hear the shadows shod in fur,

And defeat the fears in benighted life.

What’s left to us are kisses,

Fur-soft, as little bees

Who perish as they leave the hive.

Rustling through night’s limpid thickets,

Their home is deep Taygetos’ forest;

Their food is time, pulmonaria, mint.

So take for sake of joy my savage gift:

A neckless - desiccated, unseemly - strung of

Bees that died creating sun from honey.

1920

He died aged 47, on December 27th, 1938. A typhus epidemic swept the prison colony, and Mandelstam was by now a mere husk of a body. In order to get hold of his rations, his fellow prisoners concealed his death from the camp authorities for two days.

His wife, Nadezhda, who had not seen him since arrest, found out only in February, when a package she had sent her husband was returned with the note ‘Recipient is dead’.

Many former inmates recalled the poet’s commitment to his art, even at the end. But none of Mandelstam’s prison poems have survived. On this occasion, nobody managed to remember them.

Noize MC for the 2015 documentary I linked earlier, the chorus is from Mandelshtam’s Сохрани мою речь poem (“Preserve my speech”, addressed to his wife). The video description has the lyrics

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=QqtB90hsFLg

As brilliant as it is heartbreaking, your article - thank you for introducing me to such an artist. I will be following your work with interest.