Danish paper angels and ‘julehjerter’ - woven Christmas Hearts - decorating the tree, much like those my mother taught us to make.

By this point in the calendar, when I was a small boy, the excitement would have been edging quite a lot higher, and quite a lot faster, with the dawning of each day. Each little cardboard window, picked open, revealed a new illustration - a ball, a lollipop, a donkey, a star...

When I was really young, the manufacturers didn’t insert trinkets or chocolate behind the flaps of the calendar, except for perhaps into the very last compartment. But that didn’t matter one bit: each date ticked off was its own reward, with the little image uncovered behind the window calibrating the growing momentum towards the greatest day of the year. Dialling up the dB in a small boy’s beating heart.

I only realised it was Advent, 2024, early this morning when I opened the latest post from Matthew Crawford’s thoughtful Archedelia Substack (you can read the piece here). Startled, I knew the childhood iteration of me would have needed to have been in coma not to be aware that it was already December 8th. Little Christopher would have been counting the hours, not just the days!

In other words, he’d have calculated that he was now more than a week into the (excruciatingly slow!) campaign towards Christmas Day. A day closer to the far-distant promise of spilled stockings stuffed with little wonders; a meal of such proportions that Santa’s waistline needed no further explanation; and after the washing-up was done, the opening of the ‘proper presents’ - those that had lain at the foot of the tree, like time bombs of joy, all through Advent.

My brothers and I would secretly feel through the wrapping paper with eager, tiny fingers, when left to ourselves in the days running up to the Big One. Books were easy to identify, and might be hits or misses, depending on the aunt or uncle’s knowledge of our increasingly different imaginations; while ‘squashy parcels’, a term my brothers and I use to this day, suggested a sweater, or mittens, or some such dismal item - at any rate, a surefire disappointment, when it was common knowledge that for us, the very best things came in right-angled boxes and required ‘HP7’ batteries, or at least a mains supply.

The rest of the day followed a routine set down in time immemorial; meaning merely from the point at which our memories had started functioning, perhaps seven or eight years previously. A walk was called for by my father, and enforced, regardless of the weather, before it got too dark; grown-ups returned, slipped off our muddy footwear, and allowed themselves to move on to spirits with mixers, and perhaps later just spirits; the adults got louder, but were thankfully less concerned about the kids, leaving us to play with all the loot; then came spats with the siblings; an outburst of tears, sometimes brought on by thumps, and sometimes by an eruption of despairing envy; or, in the heaviest charge in the adult codex, because we were ‘over-tired’. Presaging bed time.

Then, little by little, a creeping feeling that the excitement was running down horribly fast, that the joy was trickling through one’s fingers. Far faster than you had imagined possible over the previous 24 days of off-scale anticipation and avarice.

You felt a little queasy, and not just because of the surfeit of fatty food and chocolate. You didn’t want to admit it, or name it, but there was no getting away from the truth of it: Christmas was over, with the prospect of a vast pile of unwritten ‘thank you letters’ looming upon your conscience.

Somehow, in spite of the fevered anticipation of a miraculous transaction, you felt short-changed. Wronged, even. There had to be more.

—

Thinking it over this morning, much, much later in life, I believe I have possibly come to understand what I am truly supposed to be grateful for, and what gifts bring lasting joy. After a career spent in places that were sometimes dangerous, being alive is one such gift: and for now, it ‘keeps on giving.’ I know I am fortunate.

I remembered another poem by Arseny, the father of the Soviet film director Andrei Tarkovsky. (I wrote about him in a previous post.) This poem also features in Tarkovsky’s film The Mirror, and is read out by Arseny.

It has nothing to do with the Nativity, of course. But it captures something of the hunger - the greed - I experienced as a small child at Christmas. And as a grown man, for much of my life.

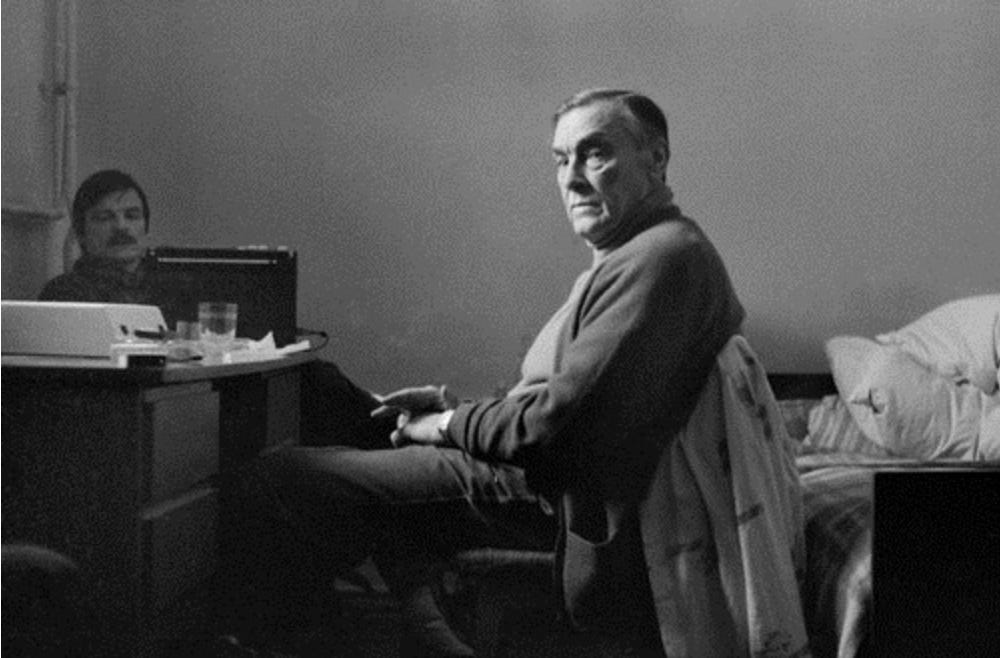

Arseny Tarkovsky, and his son Andrei ©Gueorgui Pinkhassov/Magnum

I made the translation this afternoon. It strives to capture Tarkovsky’s rhyme pattern and scansion, but loses something of the subtlety of the Russian version’s tone. Possibly, a lot of it - a native speaker could judge.

Conveying poetry is always a ‘three body problem’, and one can only do one’s best. The original is pasted below the attempted rendition.

So, the summer has gone

Just like summers before;

There’s still warmth in the sun,

But I’m longing for more.

Gifted four-leafed clovers,

I took what I saw,

Barely lifting a finger.

Yet still ask for more.

The evil and good,

That fate held in store,

Shone brightly at last.

I simply want more.

Held under its wing,

Life protected, restored:

I am utterly lucky.

And still want for more.

The leaves are unburned,

The boughs left untorn.

The day - cleansed as glass.

But there has to be more.

Arseny Tarkovsky reads his poem in The Mirror, the masterpiece by his son Andrei.

Вот и лето прошло,

Словно и не бывало.

На пригреве тепло.

Только этого мало.

Все, что сбыться могло,

Мне, как лист пятипалый,

Прямо в руки легло,

Только этого мало.

Понапрасну ни зло,

Ни добро не пропало,

Все горело светло,

Только этого мало.

Жизнь брала под крыло,

Берегла и спасала,

Мне и вправду везло.

Только этого мало.

Листьев не обожгло,

Веток не обломало...

День промыт, как стекло,

Только этого мало.

Beautiful - I remember the same advent calendars - glitter-covered pictures instead of chocolates - and that countdown. Almost as exciting as the countdown to the end of term.

Your tranlation took me away from childhood to my favourite poem - "The Second Life" by Edwin Morgan. The idea that you can reach the point where the summer has gone, and still want more. Just swap "forty" for "fifty". https://minorworksproject.wordpress.com/tag/edwin-morgan/

Christopher, I think your translation's excellent.